To kill unwanted trees, remove a ring of bark around the base.

When I bought my house, there was a multi-stemmed Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) on the property line, each trunk more than a foot in diameter. This is the “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” tree, that readily sprouts back after being cut down. When it re-grows, it usually puts up multiple new trees into the bargain, from the far flung reaches of its roots.

Well, this wasn’t Brooklyn. The trunks were gradually tearing up the fence, and the branches were getting into the overhead power lines. I convinced the neighbor to let me get rid of it.

About the first of June, I took off a band of bark around each stem, a few inches from top to bottom. Then I just waited. The neighbor had been none too fond of that tree anyway. Nobody had planted it, it had just appeared. It was gradually overshadowing both our yards.

All summer, the tree remained, to all appearances, healthy and robust. The neighbor kept asking me, “Should I start cutting it back?”

“No,” I said, “The more it grows, the faster it dies.”

The tree shed its leaves in autumn, and went through the winter unchanged. Next spring, it budded out with gusto. The new shoots grew out about ten inches. Then the whole tree shriveled up and died.

This illustrates the basic technique of girdling. You take off a ring of bark. The tree does not die right away, or even show distress. Then, some time later, it completely dies. The roots are dead, and it does not sprout back.

A common misconception about girdling is it cuts off some sort of flow to the top of the tree. and that’s what kills the tree. This is actually opposite to how girdling works.

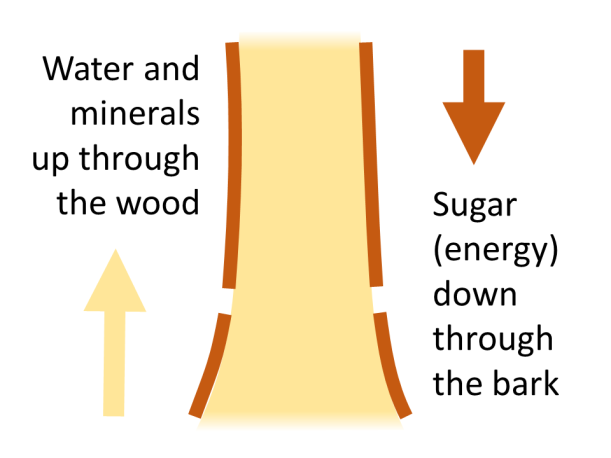

A tree conducts water and minerals up to the top through the wood. It conducts food down to the roots through the bark. When you take off the ring of bark, it stops the downward flow of food, which starves the roots. When the roots die, the tree is dead, and cannot come back.

If you simply cut a tree down, the roots are still there perfectly healthy. Most deciduous trees are very good at sprouting back from the roots.

When I bought my first house, there were a number of knobby stumps of Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila) along the outside walls. Obviously they had come up from windblown seeds. At some point, the previous owner had realized they were going to crack the foundation, and had cut them down. They sprouted back, and these sprouts in turn had been cut.

Every cut just led to more sprouts. Like a hedge. There was no way cutting was ever going to get rid of them. By cutting down the trees, the previous owner had turned the stumps into sprout factories, and created an endless round of work for himself.

I left the sprouts to grow for a year or two. I thinned out the weak shoots, leaving only a small number of strong stems. When these got to about in inch in diameter, I girdled them. Within a year, all the stumps were dead, completely dead.

Before they died, the tops grew even more vigorously then before. The stem above the girdle became noticeably thicker than the part below. The top was not sharing any food with the roots, but had everything for its own growth. Some of the shoots became so top-heavy, they started to bend over and crack at the girdle.

This illustrates that you cannot girdle twigs less than a certain size, at least not to the effect of killing a tree. The twig simply dies, as though pruned off, and the tree sprouts new ones.

At that same house, there was a box elder maple (Acer negundo) along the back alley, the trunk a few feet thick. This tree had grown up into the power lines. The top was actually getting “electo-pruned”.

The canopy was shaped flat across the top, in a shallow catenary that exactly matched the hang of the high tension wires. As the lines swung side to side in the wind, they would contact the growing twigs. Twelve thousand volts had been short circuit-ing down through that tree. It was literally keeping the twig tips burned off.

One phone call to the power company, and we were on the same page. Within a few days, that tree was cut off to the base and gone. My part of the agreement was to get rid of the roots.

I let the stump sprout back for two years. I thinned out the weak shoots, and left about a dozen strong ones. By then, the new stems were wrist- to arm-diameter at the base, and several feet tall. About the first of June, I girdled them. Within a year the stump was dead.

Sometimes the only option is to cut down a live tree. But judicious use of girdling can stop the endless cycle of re-sprouts.

What’s this about the first of June? There are easier and harder times of year to girdle. June first is the easiest time.

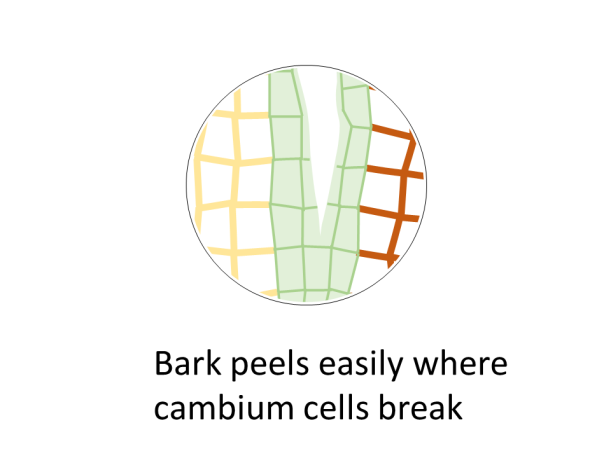

A tree has a layer of cells between the bark and the wood called “cambium”. I can’t show you the cambium, it’s microscopic.

Plant physiology books described cambium as being one cell thick, though during the growing season it can be several layers thick because the cells are actively multiplying to make more wood and bark.

During this time, the new cambium cells are thin-walled and delicate. If you go to peel the bark, it comes right off. The cells break at the cambium, which is between wood and bark. There is an old horticultural term for this, saying the bark will “slip”.

The bark gets to the stage it will slip, starting in April, when the tree buds out. It stays that way at least until early summer, while the tree is actively growing its new layer of wood for the year. During summer, if the weather gets too dry for the tree to keep growing, the bark may get tight early. At the latest, the bark will get tight again when the tree goes dormant for winter.

So, it is possible to girdle a tree any time of year. But if you do it when the bark is tight, you have to chop through the bark, down into the wood. This may not seem like such a big deal till you try it. More about that later.

The first of June for girdling is an easy date to remember. Usually, six weeks before or after June 1 works about as well. But June 1 is a good date to put on your calendar.

The tree has “spent out its bank account” growing new leaves and shoots, expecting to have the rest of summer to recoup. Instead, you come along and cut the channels.

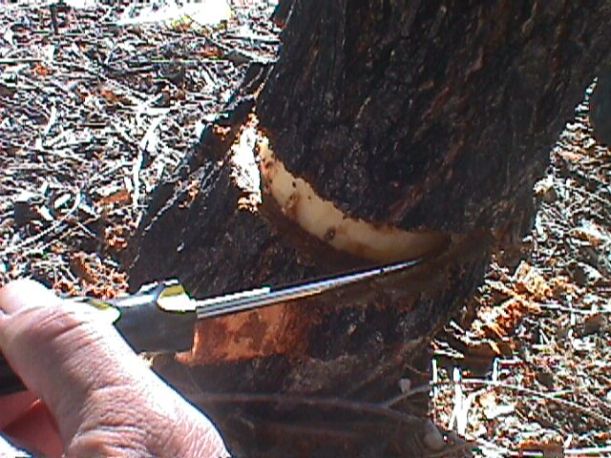

Below are pictures from girdling a Siberian elm that was getting into the neighbors’ power lines. I started by making two parallel cuts a few inches apart, all the way around the trunk.

Since this was late spring, around June 1, it was easy. I could do it with a small hand saw. I cut until I could feel that I was through the more brittle bark, and into solid wood.

Then, I pried off the ring of bark using a screwdriver. Again, since this was the time of year the bark would “slip”, it was easy. The bark nearly popped right off.

Then, I just left things. This tree showed no distress all that summer. Next spring it leafed out, and only around Easter did it start to yellow. By autumn it was dead, and we could take down the branches at our leisure.

Again, we could have girdled the tree any time of year. But when a tree is dormant, cutting bark is like chopping flint!

There are some things to watch for when girdling, to make sure it works. You don’t want all your effort to go for nothing.

Try to make sure nobody cuts off a girdled tree before it’s dead.

One time I girdled a lot of ash saplings (Fraxinus spp.) that were taking over a churchyard. It should have been easy; within a year all of them would have been dead, and easy to pull out.

I tried to communicate what I was doing but I guess people were impatient. All they saw was brush. Volunteers cut down all the saplings, and turned them into sprout factories, too big to dig out, and forever in the way of mowing.

If this happens, and you don’t want to wait for the plant to re-grow big enough to girdle again, you can starve it of light. Put, say, a bucket upside down over the stump so any sprouts grow into darkness and cannot photosynthesize. Especially for a root already weakened by girdling, this can eliminate the plant within a year. If you use a black plastic flowerpot, tape over the drain holes to exclude light, and weight it so it can’t blow away.

For a multi-trunked tree, you have to do every stem.

Below is a picture of a clump of Ailanthus sprouts that grew back after the main tree was cut down. They are all growing from the same root.

We have not yet girdled the smallest stem, but we will have to. Otherwise, that one will be able to feed the root, and keep it alive.

Take off a band of bark wide enough the tree can’t bridge the gap.

Below is a picture of a small bay laurel (Umbellularia californica) that was in the wrong place.

Notice the bark grown into the girdle from above and below. The bark spanned a significant part of the space before the tree died. If it had connected from top to bottom, the tree would have recovered.

As you can see, a thin knife slice, or even a chainsaw kerf, is not going to work as a girdle. A tree can easily bridge across that. Take out a band at least two inches high.

You have to go all the way around.

Here, we are girdling a birch (Betula spp.) that is trying to tear up two fences.

Between the wood fence slats and the chain link, there was no room to work a regular saw, so we are using a cable saw, also called a wire saw, or sportsman pocket saw. You can get one of these for a few dollars, or improvise with something like a bicycle cable. You don’t have to go through the wood, only the much softer bark.

Make sure the cambium does not regenerate bark.

Below is a picture of a girdled cherry tree, but it re-grew a stripe of bark (on the left) which bridged the girdle, and so did not die. How does this happen?

When you take off the ring of bark in spring, the bark slips at the cambium. The delicate cambium cells break, and so the bark easily peels away.

However, at this time of year, the cambium cells are actively multiplying, and the layer is more than one cell thick. Some live cells remain on the bare wood you peeled the bark from.

Usually, exposed to sunshine and air, these unprotected cells dry up and die. However, on a vigorous trunk, the wet wood can keep these cambium cells alive long enough that they can regenerate bark over themselves. Once protected, they resume their role of building bark and wood.

Sometimes these regenerated sections are only islands of bark that do not bridge the girdle. But if they form a continuous stripe, so as to bridge the gridle, the top is able to feed the roots, and so the tree does not die.

On this bridged cherry tree, the stripe regenerated on the north side, where sun did not hit, to dry up the cambium cells. To keep this from happening, there are two things you can do.

First of all, after you peel off the bark, give the wood a good scraping, up and down, all the way around, to disrupt any remaining cambium.

You don’t have to be strenuous, just thorough. You can do it with a pocket knife, or as shown above, the back (non-toothed edge) of a hand saw. You will notice a slight juicy layer rubbing off, not much actual material.

Second, come back and check the girdle a week or two later. If there are any sections of regenerating bark, scrape them off. They will come off easily, as they are on top of active cambium.

Remove any sprouts that can feed the roots.

The picture below shows a sprout coming from below a girdle. Such sprouts contribute to keeping the tree alive. Any green leaves connected to below the girdle will feed the roots.

Trunk sprouts are evident, and easily snapped off. But sometimes it’s not so obvious. Below is pictured a root sprout, some distance away from the parent tree. The source tree is visible to the right of the frame.

One clue that this sprout is connected to a major root is how vigorously it’s growing. A sprout from a seed would not likely be strong enough to put up multiple shoots, four feet tall, all in one season. In this case, the parent tree, which is in fact girdled, will not die as long as root sprouts like this are left to grow. They are providing photosynthetic energy to the roots.

Usually, if you scratch away the soil from around a shoot like this, you will see the horizontal root the sprout is coming from. Often, you can just pop the sprout off the root. This is preferable to cutting it because cutting a sprout is like trimming a hedge. It just makes the sprout branch.

For the most part, a tree that was not sending up root-sprouts before it was girdled will have little tendency to do so after. With the top in place, the tree does not rearrange its energies into root sprouts. But if a tree was already root-sprouting before it was girdled, nothing about the girdling will suppress it. You will have to manually remove the sprouts, or starve them of light.

Root sprouts and root grafts

Once I had a six-inch diameter Siberian elm tree, too crowded, between some bigger ones. I girdled it, but after two years it had not died. I dug down and found it was actually a vertical sprout off the root of one of the larger elms, coming from more than a foot below ground.

I sawed it off from that root, and chiseled the wound flat. It did not re-sprout.

This is essentially the same as taking off a large limb, flush with the trunk, leaving no stub, to discourage it from re-sprouting. If you girdle a tree but it does not die, it’s may be like this.

Some trees, such as aspen (Populus tremuloides), sassafras (Sassafras albidum) and bittercherry (Prunus emarginata), are naturally colonial. Cottonwoods (Populus trichcarpa and others) tend to be colonial when growing in riparian areas.

In a stand of these, the trunks, which appear to be separate trees, are actually only stems coming up from a common network of roots. Girdling one of these is not likely to kill it because the other stems keep the roots alive.

One time I came upon a Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) which had somehow naturally got girdled. There was a dead length of wood, spanning between the roots and the trunk. But the whole thing was still alive. Both the sections below and above had grown considerably larger diameter than the bare wood. This showed it had been that way for some years.

It was like coming upon a zombie, dead flesh dropped from the bones, but the whole thing still animate.

This macabre specimen was evidently a case of root grafting. When tree roots cross, they can sometimes grow together, and what was originally two trees then lives as one. Most conifers are not colonial. Most cannot even re-sprout from a cut stump, the Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) being an exception. But if they root graft, girdling one of the pair will not kill it.

In practice, there is little reason to girdle conifers, unless you want standing dead trees, such as for wildlife habitat. To remove a conifer, cut it off at the ground. Since it can’t re-sprout, it’s gone.

For a deciduous tree you want gone fast, you can

- cut it down and paint the stump with herbicide, or

- cut it down and grind out the stump.

But if you can wait for natural processes, girdling takes the least effort, minimal equipment, and no chemicals.

Girdling is a good option for weed trees in natural areas. No heavy equipment to lug in or pay for. No herbicides, with their hazards and regulations. Volunteers can do it, at their leisure. Then, nature takes its course.